“Everything was right about him, as if he was running on air”

When I went to interview one of the sons of Walter Rangeley some 16 years or so ago in the course of research for a biography which I was preparing of the 1936 Olympic 4 x 400 metres gold-medallist, Bill Roberts, I was told, “It’s my father you should really be writing about”. This remark was – unintentionally, I’m sure – a shade ungenerous to Roberts, whose life story turned out to be a fascinating one. Nevertheless, Michael Rangeley’s filial pride was understandable.

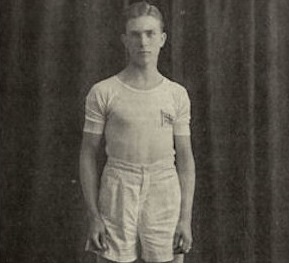

On another day at Bill Roberts’s home on the fringe of a Cheshire golf-course, by which time the old champion was aged in his late 80s, he started to reminisce to me about Walter Rangeley, his team-mate for many years in Great Britain internationals and in Salford Athletic Club’s matches and relays, and his face lit up with pleasure at the memory: “Walter was not only a great athlete. He was such an impressive person to look at. He had the smartest possible visual appearance. The way he ran was wonderful to watch. The angle of his body as he ran was absolutely right. He was our inspiration, and that wasn’t just my admiration of him when I was a lad. I’d still say now that he was the best-looking runner I ever saw – so elegant. Even when I saw Jesse Owens run later, I still thought Walter was the finest stylist I’d ever seen on a track. Everything was right about him, as if he was running on air”.

These sentiments were by no means the blurred recollections of an era long gone, exaggerated by the

passage of time. In newspaper reports of race after race of Rangeley’s over the years, his grace of movement was remarked upon and enthused over, whether he was winning one of his three Olympic medals or picking up useful household prizes at North of England sports meetings. Rangeley had been born in Salford on 14 December 1903, the son of James and Maggie Rangeley, and it was from his father that he inherited his athletic ability. James Rangeley had been a speedy Rugby League wing-threequarter for the Salford and Rochdale clubs. Young Walter joined Salford AC straight from school at the age of 16 when he had begun work as a clerk in the local branch of the Westminster Bank. At school he had won four events on the annual sports day and he almost immediately made a mark with his club by placing 3rd at both 100 yards and 220 yards at an “AAA Youth Championships” organised by the pre-World War I Olympîc silver-medallist, Eddie Owen, on behalf of Manchester AC at the city’s Fallowfield track.

The city of Salford, adjacent to Manchester, was not an obvious place in which an international athlete would grow up. In the 19th Century it had been described as “the ugly illiterate scrawl of the Industrial Revolution” and it was the model for Walter Greenwood’s 1933 novel, “Love On The Dole”. Greenwood described the setting as being “like a beleaguered city from which plundering incendiaries have recently withdrawn”. Yet, in the most touching of all athletics biographies, published in 1960, W.R. Loader, himself Northern born and bred and a sprint contemporary of Rangeley’s some 25 years before, wrote in “Testament Of A Runner” that “young men, and older men, regularly padded through dingy, gas-lit streets or past high forbidding factory walls or along the tow-paths of black polluted canals in pursuit not merely of physical fitness but of that elusive indefinable grail which lures the athlete on”.

Young Rangeley, still in his teens, helped his new club to win the medley relay at the Ashton Police Sports, and it would be the first of numerous such successes. During the 1920s relay-racing became second nature to the budding Salford sprinter, and the medley relay, with its separate stages of 880 yards, 220 yards, 220 yards and 440 yards run off in various sequences according to the meeting promoter’s fancy, was as much a feature of Great Britain’s international matches as it was of Northern works and social club meetings. Salford Harriers, which was the larger local club and was to later include the Olympic steeplechasers, George Bailey and Tom Evenson, among its membership, won the Lancashire county medley-relay title in 1921 ahead of Sefton Harriers, of Liverpool, with Salford AC, including the teenage Rangeley, in 3rd place. The British best performance for the event then stood at 3:29.8 by a star-studded Polytechnic Harriers team of 1914 which included three Olympic gold-medallists.

Among the Salford AC members were Bob Preston, who would win the Northern 880 yards in 1924, and Frank Roberts, who was an uncle of Bill Roberts. The Northern medley-relay title was won by the club in 1924 ahead of Manchester AC in 3:45.4, and by then Rangeley was on the verge of a long and illustrious international career. At the AAA Championships at Stamford Bridge, in London, he was the only Briton other than Eric Liddell to reach the 220 yards final, and though he came last of four to Howard Kinsman (South Africa), Liddell and Arthur Porritt (New Zealand) it was enough to earn him Olympic selection at the age of 20. Rangeley was to appear in 13 AAA finals (five at 100 yards, eight at 220 yards) at Stamford Bridge and the White City over 15 years, but he was never to place higher than 3rd. Having earlier in the season won the first of his Northern titles, he was to accumulate 13 in all – coincidentally, five at 100 yards and eight at 220 yards. His best AAA placing was actually at the inaugural indoor Championships of 1935 when he was 2nd at 70 yards to the future British Olympic Association secretary, Sandy Duncan,

One good reason for his restricted AAA achievements was that his employers gave him no concessions regarding time off for the championships and he often made the 200-mile journey to London by rail on the Saturday morning of the meeting. To be fair, the bank was rather more generous when it came to international selections.

At the 1924 Paris Olympics all the attention was focussed, of course, on Harold Abrahams and Eric Liddell, gold-medallists both, together with another British winner, Douglas Lowe (also Salford born), at 800 metres, and so Rangeley went out largely unnoticed in the quarter-finals of the 100 metres, but a few days later he figured in a brilliant British 4 x 100 metres team (Abrahams, Rangeley, Lancelot Royle and William Nichol in that order). Even though it was faced by only one other team, Greece, in the opening heat, the British foursome not only won by the best part of 40 metres but with a time of 42.0 also broke the World record set by the USA at the 1920 Games. Altogether, there were six heats despite the fact that there were only 15 entries, and the British quartet’s record, equalled by Holland in the third heat, was one of the shortest-lived in history as the USA ran 41.2 in heat six.

The semi-final winners the next day were the USA in another World-record 41.0 and GB in another national record of 41.8, and in the final the margin was much closer – the USA 41.0 again to Britain’s 41.2 for the silver medals. Though later equalled, this British record was not beaten until the 1952 Olympics ! There is a curious history to these “records” because the British and Dutch first-round times were not listed by the IAAF as being officially ratified until more than 20 years later, and the USA’s 41.2 in the heats and 41.0 in the semi-finals have never been ratified at all !

Four races in an afternoon during the match against France

In 1925 Rangeley took the first of that profusion of AAA 3rd places in the 100 yards, less than a yard down on Loren Murchison, of the USA, who had been in the winning Olympic relay team of the year before. The following Saturday Rangeley had a strenuous and largely successful match for England against France at Preston Park, in Brighton, with the races unusually run at metric distances. He won the 100 metres in 10.8, was 2nd at 200 metres in 21.7, and was in the winning team for the ubiquitous medley relay.

In his history of Britain’s international matches, published in 1961, Ian Buchanan wrote that “one of the most enjoyable features of the afternoon was the contest between Walter Rangeley and the French sprinters, although in the 200 metres, generally considered to be Rangeley’s best distance, he was surprisingly defeated by the Parisian, André Mourlon, whose time of 21.6sec equalled his own French record”. In truth this was a considerably better performance than Rangeley was given credit for because Mourlon had only very narrowly missed the previous year’s Olympic final, and there were but three men in the World who ran faster than he did during 1925 – Harry Evans, of the USA, led the rankings at 21.4, followed by Murchison and Kinsman, both 21.6 for 220 yards, with Rangeley equal 8th. Both Rangeley and Mourlon were in action on four occasions within a few hours at that England-France meeting as there were also heats at 200 metres to reduce the number of competitors from six to four, presumably because there were only four lanes on the curve.

Rangeley missed the 1926 match against France in Paris, but Cyril Gill and Guy Butler won the 100 and 200 metres respectively and helped the England team to a medley relay win in 3:29.8, which was intrinsically worth a second or slower than the Polytechnic record set at imperial distances 12 years before. One of Rangeley’s best performances of the season was when Britain’s fastest sprinter, Jack London, who had been born in British Guiana (now Guyana), came to the Wigan County Police Sports at Springfield Park, in Wigan, on Bank Holiday Monday, 2 August., for an invitation 100 yards. London was the only Briton to have broken 10 seconds for 100 yards during that summer and he won by half-a-yard from Rangeley in a time recorded as 9 98/100ths, according to the “Lancashire Evening Post” Such precise clockings were commonplace at Northern meetings during this era, and one can only assume that just one watch was in use.

When the two countries met the next year at Stamford Bridge Rangeley was not so successful, with 3rd and 4th places in the individual sprints, though the home team again won these and the medley relay. Rather more satisfying for Rangeley, he was to help his club regain the Northern medley relay title ahead of the mighty Salford Harriers. In all probability he would have run the 440 yards stage that day, as he often was to do over the years until Bill Roberts took over in the 1930s and Rangeley reverted to his favoured furlong.

Ironically, Salford AC suffered a severe setback just as it was establishing itself which drastically reduced its membership to a dozen or fewer. The facilities for training which the club had been granted at the local rugby-football ground at The Willows were withdrawn and the runners were forced to make their own arrangements. This sometimes amounted to using the footpath of the Manchester Ship Canal,, and among the numerous excellent atmospheric photographs which Bill Roberts was to provide me with for my book was one of him and Rangeley making the best of it as they strode along in the shadow of the Manchester gas-works in preparation for another international season to come. As it happens, this comradely scene might have been artificially contrived for the cameraman because Rangeley for the most part trained on his own.

At the 1928 AAA Championships Rangeley was a moderate 5th at 100 yards, though still behind only one other Briton, Jack London, and was then a rather distant 3rd at 220 yards to the Germans, Friedrich Wichmann (21.7) and Helmut Körnig, but he timed his form to perfection for the Olympics in Amsterdam. Admittedly, he did not advance beyond the quarter-finals of the 100 metres, in which Jack London ran superbly in the final to get the silver medal behind Canada’s Percy Williams, but in the 200 metres Rangeley produced successive runs of 22.0, 21.9, 22.0 and 21.9 to take another silver for Britain behind Williams and ahead of Körnig and the best of the Americans, Jackson Scholz – “The Times” commended Rangeley’s “beautifully easy action”. Later in August Körnig set a World record round a turn with 21.0, which makes one wonder what Rangeley was really capable of that summer. On times he actually ranked only 23rd= in the World for the year.

Another medal in the Olympic relay … then success against the USA

Altogether, Rangeley ran eight races in a week in Amsterdam, which was a tribute to his staying power in an era in which sprinters for the most part trained very sparingly, though there is evidence that he did rather more than most, and he finished off with another relay medal as the quartet of Cyril Gill, Teddy Smouha, Rangeley and London took bronze in 41.8 behind the USA and Germany. Even so, the correspondent for “The Times” said of this event and of the 4 x 400, in which the British were 5th, that “bad handing over of batons robbed Great Britain of whatever chance she possessed in both events”. A rather more polished performance was by the British Empire medley-relay team against the USA in the post-Olympics match at Stamford Bridge where Phil Edwards (Canada), Rangeley, Johnny Fitzpatrick (also Canada) and Douglas Lowe ran in sequence 440, 220, 220 and 880 and won by 18 yards in 3:22.6. It seems odd that no official World records were recognised for what was such a popular event during the 1920s and 1930s, as otherwise this performance might well have been accepted by the IAAF even though it was achieved by a composite team.

Walter Rangeley’s son, Michael, recalls that many years later his father told him that if the Olympic 200 metres final had been run a month later he would have won it. This was no idle boast – such a thing would have been entirely alien to Walter Rangeley’s nature – but was based on the form he showed in the last couple of months of the season when he ran several fast 220s, including that relay leg against the Americans.

By 1929 Bill Roberts, aged 17, had joined Salford AC, but he was not the only talented teenage recruit inspired by Rangeley’s example and so was not yet quite quick enough to get a place in the club’s medley relay team. The correspondent for the local newspaper, the “Salford Reporter”, said of the medley event at the immensely popular Rochdale Police Sports that “something of a sensation was caused by the splendid victory of Salford AC over their old rivals, the Harriers”. Bob Preston had run the opening half-mile, and then Eric Fowler and an 18-year-old future Olympian, Francis Handley, had done enough on their 220 stages for Rangeley to hold off the opposition over the closing quarter-mile. Another newspaper report that summer credited the presence of Rangeley alone for attracting 10,000 spectators to the Manchester Dock Police Sports. He also won both sprints at the Northern championships that season for the second successive year.

These local meetings in the North of England could attract a remarkably high quality of entries. For example, the annual sports organised by the Burnley & Nelson branch of the British Legion on Saturday 17 August 1929 might seem, on the face of it, to be a minor local affair. Yet it enticed along an Olympic gold-medallist, a silver-medallist and two future Empire Games champions !

The most famous of all British athletes, Lord Burghley, who had won the Olympic 400 metres hurdles the previous year, made the journey from his 16,000-acre estate at Stamford, in Lincolnshire, and won the 120 yards hurdles by 10 yards. Walter Rangeley won the 220 yards handicap. The Empire champion of the following year at that distance, Stanley Engelhart, of York Harriers, won the 100. George Bailey, the Empire steeplechase champion to be, won the two miles. The meeting was held at the Towneley greyhound-racing track, in Burnley, and the sprint events took place on a cinder surface. His Lordship surely had no great need of the first prize for his event – lavish as it was, with a value of seven guineas (£7 7 shillings) – but clearly made a day of it because his wife also graced the occasion and went along with the town’s Mayor to judge a children’s plant-growing competition afterwards.

Rangeley’s only international appearance during 1929 was in the England medley-relay team very narrowly beaten by the Germans, 3:30.8 to 3:31.2, at Stamford Bridge. This was the first match between the two countries and the visitors won rather easily by eight events to four – needless to say, the British lost all five field events. The next year was a largely blank one for Rangeley because after pressing Stanley Engelhart to half-a-yard in the Northern 100 yards at Crewe (wind-aided 9.9 to 10.0) he suffered a knee injury and missed the AAA Championships and therefore the Empire Games in Canada, where Engelhart was to win the 220. It may well be, of course, that even if Rangeley had been fit his banking employers would not have allowed him the six weeks’ or so time off required for the transatlantic sea voyage and the duration of the competition.

At the age of 26 that injury might have provided a good reason for Rangeley to retire and concentrate on his banking career. Certainly in 1931 he was absent, and the next year he managed only 5th place in the AAA 220, and so was far from gaining Olympic selection for the third time. There was some compensation at club level because after winning the Lancashire 100 yards at the Manchester County Police Sports on 25 June in an oddly precise time of 10 14/100 seconds he later in the afternoon ran the opening 440 stage of the county medley-relay championship, with Bill Roberts as one of the furlong runners, and then Frank Handley holding off another future international, Clifford Whitehead, of Salford Harriers, by only a yard on the half-mile anchor, and Manchester AC another yard back in 3rd place. There was not in those years a dedicated one-day Lancashire county championships and various events were farmed out to whichever local meeting promoter thought they would help boost his gate receipts.

Rangeley, at 28 years of age, was of course by then an international athlete of eight years’ standing, renowned the length and breadth of the North of England. Whitehead, 22, was to win the AAA 880 and make his Great Britain debut the following year. Roberts, 20, was at the start of a career which would lead to an Olympic relay gold medal. Handley, 21, was a future English native record-holder. The medley relay that June afternoon would have been a wonderfully exciting race to watch, and there was no doubt a fair number of knowledgable pundits among the crowd who in later years would relate the tale to anyone who cared to listen of having seen so many fine young athletes in the making alongside the “old master”.

Rangeley’s other races that summer were in local handicaps, where he was usually required to give such generous starts to the opposition that he had no chance of winning – for the 220 yards at the Rochdale Police Sports, for instance, he made up 18 yards on a man named W.A. Miles, of Salford Harriers, but still lost by 3½ yards. A case of Miles better, but not by miles.

Yet Rangeley was back again to international level in 1933, and he would continue to be active until a rather more pressing occurrence – the outbreak of World War II – would finally cause him to put away his spikes at the age of 35. At the Northern championships at Fallowfield, Manchester, on 17 June he beat the holder, Sid Lockett (Sheffield United Harriers), at 100 yards and was 2nd to Stanley Engelhart at 220 yards, finishing off a hectic afternoon with a 220 stage for Salford AC’s winning medley-relay team (Roberts and Handley, 2nd in the individual 440 and 880 respectively, ran those distances again). The weather that day was typically Mancunian. In other words, it was an abominable afternoon for athletics with squalls of rain lashing across the track and a violent wind buffeting the runners; so much so that winning times were reduced to such as 10.8 for Rangeley, 23.4 for Engelhart and 4:35.2 in the mile for the Olympic steeplechase silver-medallist, Tom Evenson !

The Saturday before, at the Bolton Borough Police Sports, the Salford AC quartet had easily won the medley relay and Rangeley had also triumphed in the Lancashire county 220 championship and the handicap 100 yards. For a bank clerk earning probably less than £4 a week, the prizes to the value of £15 would have represented a very rewarding afternoon’s work. A glimpse of Rangeley’s quarter-miling potential had been shown in August with another Lancashire county win at Leigh in 50.4 for equal 8th ranking in Britain alongside a future athletics journalist of genial renown, Roy Moor, among others.

At the AAA Championships Rangeley went out in the 100 yards semi-finals and his best 220 of the year would not come about until September. Even then it was a modest estimated 22.4, but that – together, no doubt, in the selectors’ minds with his unrivalled experience of the big occasion – was good enough to get him into the 4 x 100 metres relay team for the inaugural match against Italy in Milan a fortnight or so later, and he shared in the quartet’s success, though the field events again dismally let Britain down as all five were lost, and four of them by maximum points. “The Times” reported of the relay win that “Rangeley gained such yards on Gesa over the third leg that G.T. Saunders easily held off Toetti to the tape”.

1934 held special promise for Britain’s athletes, with the Empire Games taking place at the White City Stadium, in London, in August, and in the lead-up Rangeley experienced a rather odd AAA Championships. He had won the Northern 100 at Crewe in June in 9.9 and ran a 220 in the medley relay in which Salford AC, with Bill Roberts on the 440 anchor, got home by 25 yards from Salford Harriers. Rangeley then took on heats, semi-finals and finals at both 100 and 220 yards at the AAA meeting and was 4th in the former, though leading Briton, but only 5th in the latter won by the Scotsman, Robin Murdoch, from Arthur Sweeney and another Scot, Ian Young. Britain met France in Paris on 29 July and Rangeley completed a clean sweep at 200 metres behind Sweeney and Murdoch and then shared in a medley-relay success which clinched Britain’s overall victory by 66.5 points to 53.5.

At the Empire Games, a bronze medal and a then a gold

At the Empire Games Rangeley won his 100 yards heat but was then plumb last in his semi-final, only to do very much better in the 220, eventually placing 3rd in the final to Sweeney and the South African, Marthinus Theunissen (times of 21.9 and an estimated 22.0 and 22.1, as a yard covered all three). The closing day brought Rangeley a gold medal at last in the 4 x 110 yards relay, with Everard Davis, George Saunders and Arthur Sweeney as his team-mates, and once again Rangeley was a key figure in the victory on his customary third stage round the curve. Against a strong Canadian quartet, his “grand running as No.3 turned the scale in the 440 yards relay and Sweeney’s pace did the rest”, according to “The Times”, and England won by some three yards. The writer actually made a mistake here, referring not to Rangeley but to Rampling, the 440 yards champion at those Games and anchor man for the 4 x 440 relay.

In June Rangeley and Stanley Engelhart had both been credited with a 220 yards in 21.4 in Belfast, and this duly appeared in the first authoritative British all-time rankings in 1957, placing them equal 5th to Willie Applegarth, Arthur Sweeney, Cyril Holmes and John Wilkinson, but statisticians have since ruled these times out, which is a pity as Engelhart, who actually won the race, and Rangeley were perfectly capable of such a level of performance, had they been given the favourable competitive opportunity. The best 200 metres round a turn anywhere in the World that year was 21.2 by an American, Ivan Fuqua, who had been a 4 x 400 metres gold-medallist at the 1932 Olympics, and by a Swiss, Paul Hänni.

Britain’s athletes were denied the chance of taking part in the European Championships because of the bizarre decision by officials that the Empire Games provided quite enough competition for one year. As these first Championships took place in Turin in September a clear month after the Empire Games, this ruling did not make any sense at all. In Turin the 100 metres was won by Berger, of Holland, in 10.6, from Borchmeyer, of Germany, and Sir, of Hungary, both 10.7, and the 200 metres by Berger from Sir, both 21.5, with another Dutchman, Osendarp, 3rd in 21.6. The 4 x 100 went to Germany in 41.0 from Hungary, 41.4, and Holland, 41.6. These men were all very well known in Britain, as Berger had won the AAA 100 yards in 1930 and the 220 in 1933, while Sir had won the 100 in 1934 and Borchmeyer had taken both sprints for Germany in the White City match of 1933. Osendarp had finished 4th in the AAA 220 final of 1934. The British would have had a battle on their hands to get medals but at the very least deserved the opportunity to prove themselves.

Despite their aversion to the European Championships, the British Amateur Athletic Board readily sent a team of five athletes – Sweeney, Rangeley, Roberts, hurdler Don Finlay and half-miler Jack Cooper – to Sweden later in September, and when they and their manager, Arthur Turk, arrived by train in Stockholm they were greeted like heroes, photographed by the “Dagens Nyheter” newspaper as they stepped on to the platform and then again when they went for a limbering-up session at the famous stadium which had been used for the 1912 Olympics.

The meeting took place over two days, 20-21 September, and the visitors had six wins in all: Sweeney just beat Rangeley at 100 metres, 10.8 to 10.9; Rangeley then reversed the positions at 200 metres, 22.1 for both; Finlay won at 110 and 200 metres hurdles; and all three, plus Roberts, contributed to victories in a 4 x 100 metres relay and a 1000 metres medley relay consisting of successive stages of 100, 200, 300 and 400 metres. It was probably the first occasion on which the latter relay event, which was largely a Scandinavian speciality, had ever been contested by athletes from the home countries. At a subsequent meeting in very cold weather in Malmö Rangeley lost both sprints to Lennart Strandberg, a future Olympic 100 metres finalist, who ran a personal best 200 metres of 21.8.

The 1935 Northern championships meeting at the county cricket ground at Ilkeston, in Derbyshire, was a tour de force for Salford AC. Rangeley beat the rising new star, Cyril Holmes, of Manchester University, in the 100 yards (9.9w) and Engelhart and Holmes in the 220 to earn the “City of Hull Trophy” for the best performance of the meeting. Bill Roberts broke the 48-year-old championship record in the 440. Frank Handley won the 880. To cap it all, in the medley relay Rangeley, Roberts, Handley and club secretary Tommy Dignam (running one of the 220 stages) won by 15 yards. The Lancashire county 100 yards championship was held as part of the annual Wigan County Police Sports on August Bank Holiday Monday, and Rangeley won in a time reported as 9.92, which probably meant 9 92/100ths. The “Lancashire Evening Post” reporter claimed “that must stand as a record for sprinters over 30 years old”, and he may well have been right. In those days of strictly enforced amateurism, there was no material benefit to sprinters prolonging their careers to such an age. Rangeley was a rare exception. – .

Brilliant sunshine, the faintest of breezes, a firm grass track

Among the competitors that day was the future author of renown, W.R. Loader, whose 1960 autobiography, “Testament of a Runner”, evocatively related his quest to break 10 seconds for 100 yards during the 1930s, and he wrote nostalgically about the occasion: “The sun shone brilliantly. Only the faintest zephyr stirred the warm and comforting air … the grass track was crisp and firm and springy, inviting movement. Almost without direction from the brain, the limbs began to reach and thrust with their familiar power. I was doing well the thing that I knew I could do well”. Such expressiveness could equally well have applied to the running of Rangeley and Roberts that sun-blessed afternoon. Loader placed 2nd in the junior 100 yards and the following month was to win the AAA junior title.

Unfortunately, though the quality of the athletics was high, the conduct of the meeting left a lot to be desired, and E.A. Montague – the former Olympic steeplechaser who was now athletics correspondent for the “Manchester Guardian” – was incensed at the incompetence of the officials. “Never ever in the history of the NCAA has a Championship meeting been so badly run”, he fumed. He described the starting procedures as “farcical”, and reported that for the 440 yards hurdles there were only seven flights of hurdles set out at random intervals and that the steeplechase had begun before all the barriers had been put in place !

At the AAA Championships Rangeley had another of his 3rd places at 220 yards behind Osendarp and Sweeney but then beat Sweeney in the GB-France match at the White City at the end of the month. September brought the unexpected bonus of another BAAB tour as both he and Bill Roberts were late replacements in a five-man group which set off by sea-ferry from Newcastle to Bergen for two meetings in Norway – the other athletes were Finlay and the Scottish middle-distance men, Bobby Graham and Tom Riddell. Despite heavy rain which threatened to bring the meeting to a premature close, Rangeley showed just what he could do on a Continental track with a win at 100 metres in 10.6 at the coastal town of Haugesund, some 100 miles or so from Oslo, on 12 September and a wind-aided 10.5 in Oslo three days later, plus an unstrained 21.8 200 metres in the heats and the final at the latter meeting.

His 10.6 equalled the British best (no official metric records for Britain’s athletes in those days) set three times at the 1924 Olympics by Harold Abrahams and then by Jack London at the 1928 Games and by Arthur Sweeney a month earlier in 1935 in the Germany-GB match in Munich. Only four other Europeans had faster legal times than Rangeley that year – Hänni, of Switzerland, at 10.4 and Osendarp, Gerd Hornberger (Germany) and József Kovács (Hungary) at 10.5.

After another narrow 220 yards loss to Engelhart at the 1936 RUC Sports in Belfast, 21.8 for both, and then 4th place at the AAA Championships, Rangeley made his third Olympic Games appearance at the age of 32. There was no medal to be had this time, but he was the outstanding performer again in the sprint relay, and “The Times” said that he ran “a beautifully smooth third stretch”. However, this was in the first-round heats, not the final, and with Sweeney absent through injury Britain went out in 4th place to Holland, Argentina and Hungary in 42.4. Charles Wiard, of Blackheath Harriers, was the lead-off man, while Don Finlay, the 110 metres hurdles silver-medallist of two days before, was on the second stage and Alan Pennington, of Achilles, ran the anchor. Neither Wiard nor Pennington had any previous experience of international relay-racing and the versatile Finlay’s only other such outings had again been as an emergency replacement at the 1932 Olympics and on tour in Sweden in 1935.

No possible blame could be apportioned to Rangeley for the disappointing British performance. In any case, it was a remarkable achievement to appear in a third Olympics in 12 years. For a professional in the 21st Century it would be noteworthy, but for an amateur in the inter-war years it was exceptional. The only other British Olympian athlete over the same time-span was the Yorkshire distance-runner, Ernie Harper, who coincidentally was also a silver-medallist – in the 1936 marathon – and also missed the 1932 Games.

More appearances in AAA finals as wartime approached

From 1935 to 1939 Rangeley had continued to regularly figure in AAA finals: at 100 yards 5th in 1935 and again in 1937; at 220 yards 3rd in 1935, 4th in 1936, 6th in 1937 and 4th again in 1939. Such was the regard in which he was held that on his last appearance less than two months before war broke out “The Times” suggested that “Rangeley, if he could have won, would have shaken the White City to its foundations”. By now the leading British sprinter was Cyril Holmes, from Manchester, who had won both the 100 and 220 at the 1938 British Empire Games in Sydney and would continue to race throughout the war while serving as an army physical training instructor. Holmes beat Sweeney for the 1939 AAA title at 220 yards, and other sprint competitors at the Championships that year included a

17-year-old Nottinghamshire schoolboy, Jack Archer, who would become European 100 metres champion in 1946.

Walter Rangeley continued to work for the Westminster Bank and eventually rose to the position of chief clerk at the Manchester office. Both of his sons, Colin and Michael, inherited some of their father’s turn of speed, and Colin was 2nd in the Cheshire senior 100 yards of 1954, when Michael won the junior 100 yards and long jump, and was 1st in 1955. They then both concentrated on their teaching careers – French for Colin, music for Michael. Their father was keenly interested in classical music and played the piano at home.

Colin, born in 1931, clearly remembers seeing his father compete and the impact he had on those who watched him: “He was a big name. When he was running, the crowds came. He had terrific acceleration in the last 20 yards and for a man of 5ft 10 or 5ft 11 he had a very long stride – I think 8ft 6. He kept his hands fairly low and he seemed to glide past everyone. He ran some 440s for the club, but really he thought it was much too far. Of course, he didn’t train as they do today, but he would do some starting practice and run one or two 300s. He would also run the straights flat out and jog the bends for as long as he felt inclined in a form of interval training. He took his athletics seriously, but he didn’t regard it as the most important thing in life”.

Michael, born in 1936, started running seriously at Sale Grammar School at the age of 14 or so and recalls Salford AC training sessions with his father in attendance: “He never pushed me. He would simply say, ‘Try doing this’. It was all very informal. Later on, when I started running at the same handicap meetings in which my father had competed and had often won people would ask me, ‘Are you going to do the same ?’ In the 220 yards handicap races in which he had taken part there would be numerous starters and when it came to the home straight he would shout, ‘I’m coming through !’ and the ranks of runners would part in front of him ! In our present day he would have been a mega-star ”.

One interesting evaluation to be made of Walter Rangeley’s track career is that he competed in 31 different races for Great Britain, and this was a total which was equalled in pre-war years only by Don Finlay and which was ahead of Olympic gold-medallists Lord Burghley and Godfrey Brown (26 each). Two other Olympic champions from Britain in those inter-war years, Harold Abrahams and Douglas Lowe, managed only the same total of 31 races between the two of them. But the bare statistics trace but a small part of the Rangeley legacy.

After he and his wife retired from their Ashton on Mersey home to North Wales, he died at the age of 78 on 16 March 1982, and the chapel was packed for his funeral service at Manchester Crematorium a week later, with many more people standing outside to pay their respects. Maurice Scarr, a fellow British international sprinter who had joined Salford AC and had become a close friend of Rangeley’s, continuing to talk to him regularly by phone throughout their lives, spoke of him with great affection at the funeral:

“First and foremost Walter Rangeley was a family man. The centre of his life was the home which he and Hilda made together and which provided the right support and encouragement for his boys as they grew up … His activities were many and varied. He loved his garden, which was always a credit to him and a source of enjoyment to others. He loved walking and could wax eloquent about the special thrill of walking in the fells. Above all, he was a keen sportsman with a special talent for athletics in which he achieved great distinction. He was also a calm and resourceful man with a passionate interest in classical music. His enthusiasm was infectious and he liked nothing better than to share his love of music with a friend. Walter will be remembered with respect, gratitude, love and affection”.

A conclusion by the author

Among the half-dozen books that I have written over the years about athletics or Olympic Games history the biography of Bill Roberts, in which frequent references were made to Walter Rangeley, is one of which I’m particularly proud. I thought that it said a lot about athletics in Britain in the years between World War I and World War II which had not appeared in print before, and Roberts was such an interesting character – Olympic champion, successful self-made business entrepreneur, musician and band-leader, elegant man about town. Unfortunately, the enterprising Manchester-based publisher of “The Iron In His Soul” (2002) was forced out of business a year or so later, victim not of his own shortcomings (nor mine, for that matter !) but of cash-flow problems, and the book has become something of a collector’s item. It’s particularly satisfying, then, for me to have been able to revive some of its passages in writing about Rangeley, and I think this rather proves that Michael Rangeley was right. Someone should have written his father’s life story a long time ago.

The Rangeley family has a website, including photographs, at www.rangeleyfamilytree.co.uk.

Bob Phillips